A few weeks ago my Birkenstocks busted. The leather strap that fits around my achilles gave up the ghost. These are the Birkenstocks that have followed me since high school. I’ve had them repaired no less than three times, once in high school, once in college, and once in seminary. When I send them in, usually the only salvageable part is the leather with its trusty bronze buckles. Finally, however, the leather buckled while I was walking to work one morning, the dislocated strap flagellating my heel as I marched on top of it–payback for years of being trodden on.

I continued wearing them but the flapping strap was a constant reminder to do something. What I needed was a cobbler. Is that still a vocation? When’s the last time I passed by a cobbler’s shop in the US of A or England or France? Surely if I were in the West, I would have to send my sandals off to a “certified Birk repairman,” the cost of which would most likely turn me off the idea of righting the niggling strap. So, I did the next sensible thing and turned to our compound’s security guard, an Ewondo of experience and extensive local knowledge.

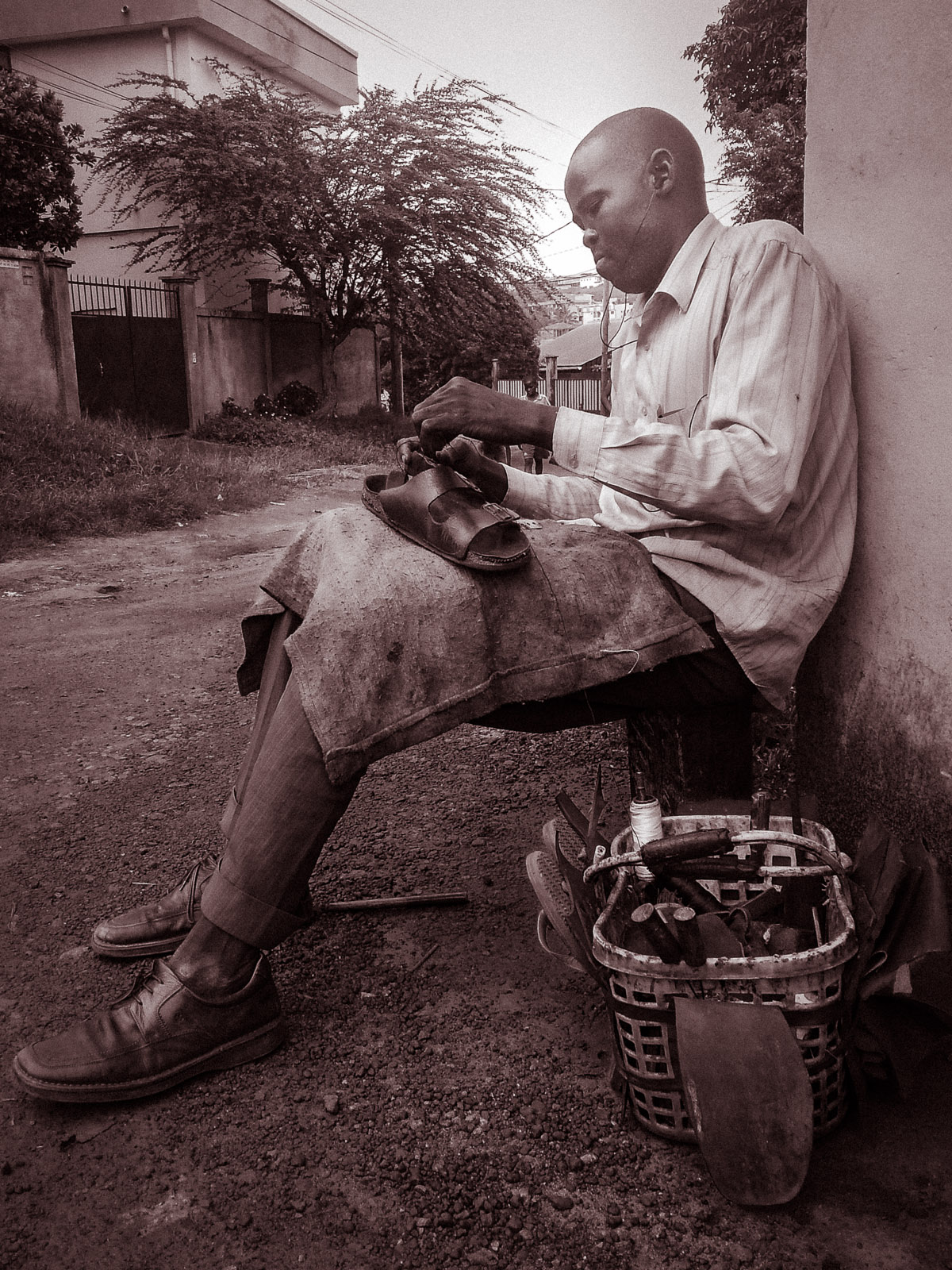

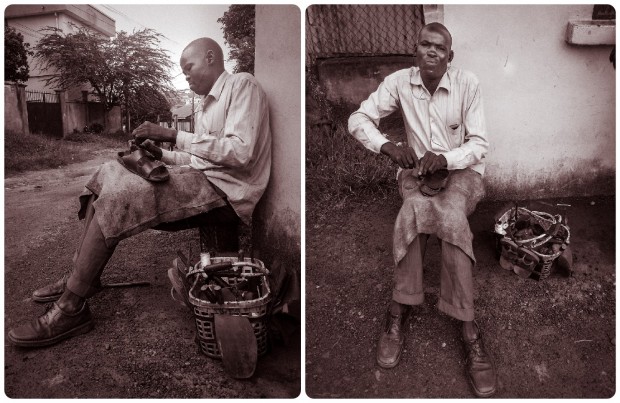

The next thing to happen was a lunchtime knock at the door. “Quick, come out to the gate. I stopped the peripatetic cobbler for you when he passed by.” It took me a moment to process the French I was hearing: un cordonnier ambulant. Yep, that would be a peripatetic cobbler, a mobile shoe repairman. Here they walk around advertising their services by clanking awls together, creating an awful racket. But now he sat outside my compound, poised to puncture. I handed him the problem sandal and after a moment’s inspection had a quote: 300 francs. 60 cents. His price.

Community is not a buzzword in Africa. It’s life and it’s lived. I’ve been led to contemplate community a lot lately, especially since recently finishing the very moving and thought-provoking reflections of a brother on the loss of his sister to cancer in a rural Louisiana community. Accomplished journalist Rod Dreher has indeed authored a good read with The Little Way of Ruthie Leming: A Southern Girl, a Small Town, and the Secret of a Good Life. Allow me to commend it to you as means to focus our attention on family, community, roots, faith and tough times. Dreher notes near the end that

Contemporary culture encourages us to make islands of ourselves for the sake of self-fulfillment, of career advancement, of entertainment, of diversion, and all the demands of the sovereign self. When suffering and death come for you— and it will— you want to be in a place where you know, and are known. You want— no, you need— to be able to say, as Mike [the author’s widowed brother-in-law] did, “We’re leaning, but we’re leaning on each other” (p. 209).

As we plan our next move to a new part of the country, the recurrent advice we hear is to get involved in the community. Friends make defenders if and when something goes down. Local relationships are security. But more than that, friends–relationships–make life livable. Communities will lean, but those within it have each other to lean on, whether that concerns a busted Birkenstock, a late sister, a game of soccer or borrowing carrots.

CommentsOnToast