Last week I helped teach the second round in our Bible Translation Principles Course, a series of six one week courses spread out over a year which seeks to train mother-tongue translators. (A mother tongue translator is a national who develops the necessary capacities to translate into his or her own language.) Twenty-one participants representing six languages were in attendance. These men and women had been specially designated by their respective community’s language committees to come to our training center to participate in this course. They bring with them different life experiences and levels of education, but with a desire to develop their language. Here’s a peak into what you we did during the week. Special thanks to our friend and colleague Andreas for many of the pictures.

Each morning we started off with a time of singing, Scripture reading and prayer, always led by the participants. A crowd favorite was cantique no. 505: Tout joyeux. I can still hear it’s memorable refrain resounding in my brain: “Gloire à Dieu! Gloire à Dieu! Que ce chant retentisse en tout lieu!”

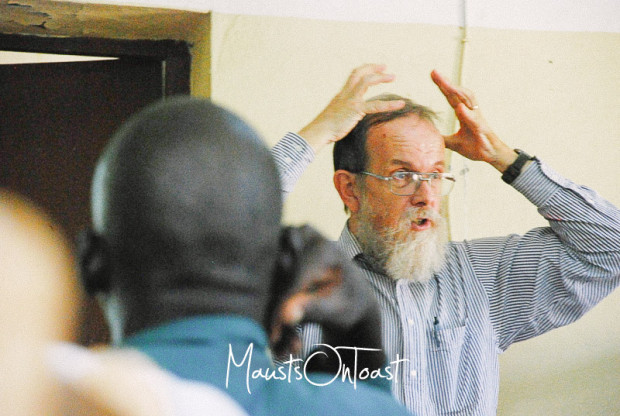

Next we jumped into two morning teaching blocks separated by a much-needed coffee break. My British colleague, Dr. Smith, directed the morning sessions. He’s a man of formidably towering intellect who knows how to put the cookies on the bottom shelf. His nearly two decades of hands-on field experience give him an edge on the translation difficulties and cultural gaps that our participants will likely face while taking their readers into the world of the Bible. You can see me tucked away in the back corner grading homework, in this case back translations of translations of 1 Samuel 16-17 that participants were to have completed since the last course.

(A back translation is one method we translation consultants use to check translations into languages that we don’t speak. First, the mother-tongue translator translates the passage into his language. Then, to check for accuracy [e.g., additions, omissions, and transformations], the translator has someone else who speaks his language translate what he’s translated back into a language that is shared with the consultant (for us, most often that’s French). Thus the process looks like this: French (with original language helps) –> Cameroonian language –> French. I like to tell mother tongue translators that back translations are like eye glasses for us translation consultants; that is, they help us see into their language.)

The kids love coming to coffee break to mix up murky brews of sugar-rocked tea. And then, thanks to the sugar rush no doubt, they climb trees, one more comfortably than the other.

After exercising our minds during the morning hours, noon thirty quickly rolls around and it’s time to share lunch together. Poppy enjoyed passing out plates while wearing fairy wings.

The afternoon sessions were led by yours truly. We discussed different methods the translators can use to test the clarity and naturalness of their translations in the village with members of their communities. One method asks speakers to read a passage aloud while the translator listens attentively for places where the reader stumbles or hesitates. This may signal a spot where the translation isn’t clear or natural.

When it rained, we rolled up our pant legs and put out the buckets.

My afternoon teaching sessions were followed by group discussions on difficulties in the passage they were translating during the week: the ever-popular David and Goliath narrative. As a group, we would read the passage aloud several times. This would help us spot words and phrases that were particularly tricky. Part of what I’m aiming at here is to get them to ask questions of the text like Why do the French translations all differ at this one particular spot? or What does this underlying Hebrew word mean? or Given the verbs in this phrase, which action preceded which? Good Bible study is all about asking good questions and then knowing where to go to find possible answers.

Here are some interesting things we worked through in their translations of the David and Goliath story:

A champion named Goliath from Gath came out from the Philistine camp. He was more than nine feet tall. He had a bronze helmet on his head and wore bronze scale-armor weighing one hundred twenty-five pounds. He had bronze plates on his shins, and a bronze scimitar hung on his back. His spear shaft was as strong as the bar on a weaver’s loom, and its iron head weighed fifteen pounds. His shield-bearer walked in front of him. (1 Sam. 17:4-7 CEB)

In describing Goliath’s weaponry and armor, there are some strange words in there! On top of that, the meaning of the Hebrew word for one of the weapons is uncertain. Just imagine you spoke a language of 15,000 people that did not have its own dictionary or encyclopedia to consult. Would you be able to easily come up with words like bronze, helmet, scale-armor, scimitar, spear shaft, weaver’s loom, iron, and shield-bearer? I myself had to look up some of the words in the French translation (and Hebrew!) before I got the technical picture.

[Goliath’s] shield-bearer walked in front of him. (1 Sam 17:7)

One language team wanted to know why Goliath had to have someone carry his shield for him. In their culture, it was a sign of weakness if a warrior was unable to carry all of his own weaponry. Surely then Goliath was not as big and bad as the passage was making out if he had to have a shield caddy lug around his battle gear. Here was a verse where this team would need to put a footnote clarifying for their readers that in the culture of the time having a shield-bearer meant that a warrior was celebrated enough that he didn’t have to carry all his gear by himself and plus he was well-protected by having a separate person protect him from enemy combatants with a large standing shield. Without the note, the translation risks communicating the opposite sense!

Compare the Common English Bible and the English Standard Version of 1 Samuel 17:6.

He had bronze plates on his shins, and a bronze scimitar hung on his back. (CEB)

And he had bronze armor on his legs, and a javelin of bronze slung between his shoulders. (ESV)

Spot any key difference? What did Goliath have slung on his back? Was it a scimitar (a curvy-looking sword) or a javelin (a throwing spear)? The meaning of the underlying Hebrew word is actually uncertain. We get the idea, however, that the weapon described here is one that can be used to either stab/slash or to throw. Most contemporary translations just pick one of these aspects and go with it. Slashing = scimitar. Throwing = javelin. Which would we opt for? During our course, my colleague Dr. Smith reminded the participants that in many of their cultures their warrior ancestors used to have a weapon that matched both aspects of this slashing-throwing description. (He had seen one hanging on the wall in a local restaurant.) He and I acted out how the weapon was used. I approached him with my laptop case hoisted as a shield and he attacked with his imaginary ancestral weapon. Fortunately, we drew laughs rather than blood. After the demonstration, many translators instantly came up with the corresponding word in their language. Others, mostly the younger translators, were still uncertain. We recommended they chat with their elders about the (not so) good ole days. Even if you have no print dictionary or encyclopedia, you may still have mental museums in your elders. It’s important to take advantage of them before they disappear.

Here’s a picture of one team talking through their translation together, the only team with a female translator. Even though she had to excuse her self periodically from the lectures to nurse her baby b0y, she consistently scored better on the daily quizzes than many of the men! You go, sister!

In case you can’t tell, I had a blast last week! At the end of September we’ll welcome all the participants back to the training center for round three. In the meantime, I’ve got a lot of prep to do!

CommentsOnToast